Michael Nicholson—now Assistant Professor in the Department of English at McGill University—joined us as an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow in the Humanities during the 2016-2017 year on Time, Rhythm, and Pace. His project was titled After Time: Romanticism and Anachronism. Michael provides an overview of the project he worked on while at the JHI and some insight into his fellowship experience. He also updates us about his current work and shares why he thinks the humanities are important.

After Time: Romanticism and Anachronism

Historical and historicist works from the seventeenth century to the present portray anachronism as the sign of error and backwardness. At the JHI, I worked on After Time: Romanticism and Anachronism, a literary history of anachronism which alternatively argues that intentional anachronism is the mark of prescience and modernity.

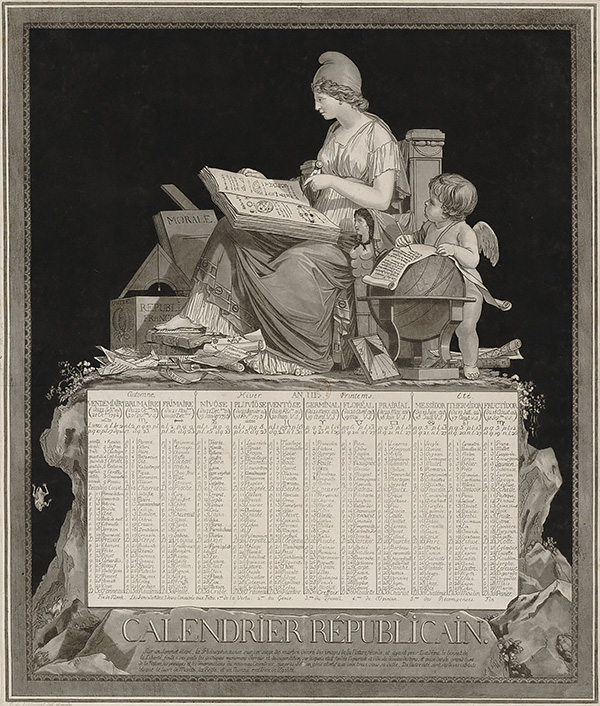

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Europe experimented with new technological modes of measuring and telling time with clock and calendar: Thomas Tompion, the “Father of English Watchmaking,” manufactured thousands of timepieces in the 1700s, Britain erased eleven days from the calendar in the 1750s, France turned back the hands of time to Year One in the 1790s, and the British Railway Clearing House adopted Greenwich Mean Time in the 1840s.

At the same time, English poets from a broad range of backgrounds were developing new poetic strategies of anachronism—from the Greek ἀνά (ana: against) and χρόνος (chronos: time)—to contest the increasing dominance of what I term “imperial time”: the new clock-based, machine-regulated, and strictly standardized temporality used to enforce a forward-moving imperial narrative. Together, Romantic poets offer us new ways of understanding the power of poetic form to reshape time’s binds.

The JHI Experience

The Jackman Humanities Institute was the ideal intellectual arena in which to explore my interest in the central role of Romantic poetry in asserting powerfully untimely rhythms. The wit and wisdom of my colleagues continually renewed and energized my scholarship in fortuitous ways.

Elizabeth Harvey, Rebecca Comay, Sherry Farrell Racette, Erag Ramizi, Erin Soros, Atreyee Majumder, Chris Dingwall, and countless others provided insights, suggestions, readings, and critiques that have reshaped my project.

As these diverse collaborative endeavors make clear, I found intellectual comrades, ideal readers, and fast friends among my many challenging, generous, and brilliant colleagues. I was also paired with an accomplished and convivial faculty mentor in Alan Bewell, a fellow Romanticist whose unfailing support, advice, and erudition has enriched my research and teaching.

Besides the collegial yet rigorous Jackman lunch seminars which perpetually extended my range of intellectual vision—my participation in the “Nineteenth-Century Time” working group afforded me the opportunity to interact with a wide range of distinguished humanities faculty from across the university, including Profs. Sherry D. Lee and Ellen Lockhart (musicology).

This lively interdisciplinary community even made it possible for me to invite an English colleague from Concordia University to conduct a seminar on Romanticism, literary theory, and acceleration.

I found my time as a JHI Fellow valuable precisely because of its structure and diversity. In my experience, it's rare to find an intellectual space where scholars from various disciplines, backgrounds, and academic levels—from undergraduates to senior faculty fellows—engage in rigorous (and regular) conversation on particular topics of common interest.

Our discussions were also enriched by the participation of the JHI’s first Indigenous Faculty Scholar, Prof. Sherry Farrell Racette, and the 2016-17 Distinguished Visiting Fellow, Prof. Christine Ross.

I truly enjoyed the time I spent in my office, making trips to the shared kitchen to refresh my cup of tea, comparing notes with staff and colleagues, and feverishly writing up my monograph on British Romantic poetry.

I have fond memories of JHI lunches and talks, as regular interactions with other JHI Fellows—professors, postdocs, graduate and undergraduate students alike—shaped and refined my thinking, allowing me to examine the concepts of time, rhythm, and pace from a variety of disciplinary perspectives.

I particularly enjoyed hearing a selection of what would become postdoctoral fellow Atreyee Majumder's monograph, Time, Space, and Capital in India: Longing and Belonging in an Urban-Industrial Hinterland (Routledge 2018). Atreyee’s presentation challenged me to think about temporality from an anthropological and spatial perspective.

Current Work

Current Work

Besides teaching courses on nineteenth-century British literature, early ecologies, science fiction, empire, and poetry at McGill University, I am currently directing a SSHRC Insight Development grant, “Living Calendars: Romanticism and Organic Time,” investigating the history of organic clocks and poetic calendars.

Recent articles have focused on the scientific practice of Shelley's creature, Byron's queer temporalities, Clare's poetics of stress, Romantic entomology, and Melville’s representations of disability.

I also recently completed a fellowship from the Huntington Library on the temporality of slavery and transportation.

Finally, I am currently co-directing the Montreal International Poetry Prize, which awards $20,000 CAD to the writer of a single poem. The inaugural 2020 McGill competition, judged by Pulitzer Prize-winning African American poet Yusef Komunyakaa, received over 4,900 entries from 107 countries.

Importance of the Humanities

I find that in uncertain times such as the present, we need the humanities more than ever. Few spaces in our contemporary world—defined by political crisis and ecological calamity—encourage us to slow down and reflect on critical questions about what it means to be human.

The numerous recent articles marking the return to poetry during a time of pandemic, for example, attest to the unique role played by the humanities play in times of crisis. In a humanities classroom—whether physical or virtual—students and professors engage in spirited discussion, lively exchanges shaped by critical thinking.

For me, the value of a humanities degree lies not in the particulars, but in the broad strokes—years after graduation a student may not recall the fine-grained details of her thesis on William Wordsworth's "We Are Seven," but will still be able to pick apart faulty ethical logic and formal analysis, carefully forming opinions and values shaped by sound reasoning.